Your brain “wakes up” more than 100 times each night. That’s normal — and maybe good

It’s common for humans to bemoan a night of fragmented sleep and prize one that’s completely uninterrupted, but a study conducted on mice — which share basic sleep mechanisms with us — suggests that brief, repeated “wake-ups” during sleep are completely normal, and may actually augur well for one’s memory. The research was published in Nature Neuroscience.

Sleepy head

Sleep is a complex neurological process characterized by shifting brain patterns, fluids flushing in and out of the skull, and a drop in body temperature, all with the apparent aim of restoring the brain as its waking functions are disabled.

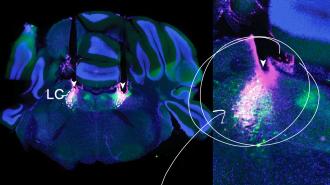

In this process, the hormone norepinephrine appears to play a significant role, even though it’s released at lower levels during sleep compared to when we’re awake. Observing the brains of mice as the critters slept, scientists from the University of Copenhagen watched norepinephrine (also called noradrenaline) levels rise and fall in a steady, oscillatory pattern, and noticed that this rhythm coincided with frequent, fleeting spurts of arousal in the brain.

“We have learned that noradrenaline causes you to wake up more than 100 times a night,” co-first author Celia Kjærby, an assistant professor from the Center for Translational Neuromedicine, said in a statement.

“Neurologically, you do wake up, because your brain activity during these very brief moments is the same as when you are awake. But the moment is so brief that the sleeper will not notice,” PhD student Mie Andersen, the other co-first author of the study, added.

Furthermore, the researchers noticed that when norepinephrine’s oscillation had a greater amplitude — meaning a larger disparity between peak levels of the hormone and the lowest levels — it led to more complete awakenings but also increased the frequency of sleep spindles, brain wave patterns experienced during sleep associated with learning and memory processing.

“You could say that the short awakenings reset the brain so that it is ready to store memory when you dive back into sleep,” Maiken Nedergaard, a Professor of Glial Cell Biology at the University of Copenhagen, speculated.

Indeed, when the researchers artificially reduced the amplitude of norepinephrine’s oscillation in mice’s sleeping brains, either through genetic engineering or pharmaceuticals, they found that the mice performed worse on memory tests compared to unaltered controls.

Of mice and men

Though mice studies rarely translate perfectly to humans, the researchers think that theirs should as similar biological sleep mechanisms are observed among mammals. Creating a technique in humans to fine-tune norepinephrine oscillations as we sleep “might provide a powerful therapeutic tool in promoting the memory-enhancing segments of sleep,” the researchers write.

Another takeaway from the study is that we shouldn’t expect our sleep to be seamless. Brief wake-ups, whether noticed or unnoticed, seem to be quite normal and are generally not a cause for concern unless triggered by a disorder such as sleep apnea.

“Of course, it is not good to be sleepless for extended periods, but our study suggests that short-term awakenings are a natural part of sleep phases related to memory. It may even mean that you have slept really well,” first author Kjærby stated.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.