One dose CRISPR therapy cuts cholesterol by up to 55%

The first-in-humans trial of a CRISPR-based cholesterol treatment has delivered promising results, with one participant in the small study experiencing a 55% reduction in their cholesterol levels. However, the company will need to show that the treatment is safe, after concerning safety data.

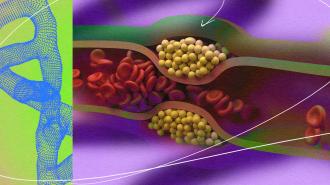

The world’s top killer: Cholesterol is a waxy substance made by our livers and found in certain foods. It comes in two forms, HDL and LDL, and while having high levels of HDL cholesterol in your blood appears beneficial, high levels of LDL cholesterol will eventually block your arteries, leading to cardiovascular disease, heart attacks, and strokes.

This kind of heart disease is the number one cause of death in the US and around the world, and even non-fatal heart attacks and strokes can cause severe pain and disability for millions of others.

“There are people walking around who have the [PCSK9] gene naturally turned off … and are resistant to heart attack.”

Sekar Kathiresan

There are ways to lower high LDL levels, but none is ideal, and for some people, they still aren’t enough to keep their cholesterol levels in a healthy range.

Pills called statins are the most common cholesterol treatment, but they have to be taken daily and sometimes cause intolerable side effects. Newer injectable meds can be administered just twice yearly, but those are expensive and not always covered by insurance. A healthier diet, meanwhile, can help, but that’s also very tough in practice for many people.

The idea: Boston-based biotech firm Verve Therapeutics is developing what could be a one-and-done, life-long cholesterol treatment.

This therapy, called VERVE-101, is designed to deactivate a gene in the liver that controls the production of PCSK9, a protein that regulates the amount of LDL in the blood.

“There are people walking around who have the [PCSK9] gene naturally turned off,” Verve CEO Sekar Kathiresan told Freethink. “They have very low levels of cholesterol in the blood and are resistant to heart attack, so the company is basically built off of that insight.”

VERVE-101 permanently deactivates the PCSK9 gene in the liver by using CRISPR to change just one letter in its DNA. This technique is called “base editing,” and Verve’s trial is the first to test it in humans.

What’s new? In trials on monkeys, VERVE-101 reduced LDL levels by nearly 70% after just two weeks, and they remained low for 2.5 years.

Verve has now shared the interim data for heart-1, a phase 1b trial of the therapy involving 10 people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH), a potentially life-threatening genetic disorder that causes very high LDL for a person’s entire life.

“This study reveals the potential for a new treatment option — a single-course therapy that may lead to deep LDL-C lowering for decades.”

Andrew M. Bellinger

According to the company, just one dose of the cholesterol treatment could lower LDL levels by up to 55% after 28 days. The benefit persisted through six months of follow up, too.

“Instead of daily pills or intermittent injections over decades to lower bad cholesterol, this study reveals the potential for a new treatment option — a single-course therapy that may lead to deep LDL-C lowering for decades,” said Verve’s CSO Andrew M. Bellinger.

The details (and the safety concerns): The researchers tested the cholesterol treatment as an infusion at four different dosages: 0.1 mg/kg, 0.3 mg/kg, 0.45 mg/kg, or 0.6 mg/kg. Each dosing group included three people, except the highest dose — only one person received it.

Only the two higher doses were expected to have a therapeutic effect — the lower doses were included to assess safety and tolerability — and the person who experienced the 55% reduction in their LDL levels received the highest dose.

Two people in the .45 mg/kg group experienced reductions of 48% and 39%. The third had a heart attack the day after treatment and did not have their data included in the report. That person was having chest pains before receiving the gene therapy, but didn’t tell the researchers, according to Verve.

No one in the lower dose groups experienced treatment-related adverse events, but mild and moderate adverse events occurred in the higher dose groups. These were temporary, and included infusion site reactions and elevated liver enzyme levels.

Five weeks after treatment, however, one person in the .3 mg/kg group had a fatal heart attack, although investigators determined it was not related to the treatment.

History lesson: This was a very small study, and 2 out of 10 participants experiencing heart attacks after treatment is a serious concern — Verve’s stock plummeted after the trial results were announced.

However, because gene editing is still very new, the FDA only allows researchers to enroll people with severe, advanced disease in first-in-human trials.

“Their arteries have been clogging from birth, and so they have a lot to potentially gain.”

Sekar Kathiresan

The fact that two people had heart attacks isn’t necessarily surprising when you consider these were all people with serious heart disease prior to starting the trial — nine had already undergone surgeries to improve blood flow to their hearts, and four had had prior heart attacks. And despite taking the maximum dose of statins, their average LDL cholesterol entering the trial was 193 mg/dL, compared to a goal of <70 mg/dL for high-risk patients.

“These patients, their cholesterol has been high their whole lives,” said Kathiresan. “Their arteries have been clogging from birth, and so they have a lot to potentially gain from a treatment that would reduce their cholesterol dramatically and durably.”

Nonetheless, Verve will need to prove to regulators and the public that its treatment is safe enough for the benefits to be worth the risks.

Looking ahead: Verve is now enrolling more participants into the trial’s 0.45 mg/kg and 0.6 mg/kg cohorts. Its goal is to use information from this stage to determine the ideal dose of its cholesterol treatment to test in a larger trial in 2024.

While Verve is currently focusing on people with HeFH, because they have the most to gain, its ultimate goal is to have a CRISPR therapy that can durably reduce anyone’s LDL cholesterol levels for life.

“We’re looking to take this new approach to treating not just a rare disease or cancer — which is often what a lot of gene-editing therapies are focused on — but rather to literally the most common cause of death in the world,” said Kathiresan.

“But we’re going to be doing it in a very measured way, a graduated way, starting with a genetic form of the disease and then expanding out to larger groups, assuming after showing that it can work and be safe,” he continued.

Journalist B. David Zarley contributed to this report.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].