New MS treatment targets the gut microbiome

A new study suggests that we may be able to prevent chronic inflammation in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients in a totally new way, by manipulating their gut microbiomes — the unique collection of microbes that live in our digestive tracts and play an important role in our health.

“We are approaching the search for multiple sclerosis therapeutics from a new direction,” said lead researcher Andrea Merchak from the University of Virginia (UVA).

Chronic inflammation: The immune system fights infections and heals injuries by sending inflammatory cells to the site of the problem. This process, inflammation, can cause pain, swelling, or other side effects, but ultimately, it’s for the greater good.

Sometimes, though, inflammation happens when a person isn’t sick — this is called chronic inflammation, and it can play a role in many health issues, including Alzheimer’s, autoimmune conditions, heart disease, and cancer.

“We are approaching the search for multiple sclerosis therapeutics from a new direction.”

Andrea Merchak

The challenge: Chronic inflammation is also a hallmark of multiple sclerosis (MS).

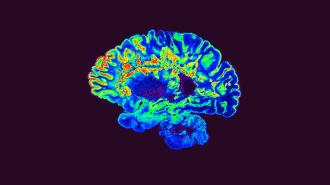

This disorder, which affects nearly 1 million people in the US, causes the immune system to attack the substance covering the nerve fibers of the brain and spinal cord. This can cause inflammation in the brain, leading to pain, vision loss, cognitive problems, movement issues, and more.

While not usually fatal, there’s no cure for MS. All doctors and patients can do is treat the symptoms and try to slow progression, sometimes with immunosuppressant drugs that cause their own side effects and leave patients vulnerable to infections.

The study: Past studies have suggested that a protein called AHR appears to play a role in MS, but researchers haven’t been exactly sure how.

For a new study, published in PLOS Biology, UVA researchers discovered that AHR seems to trigger the production of inflammation-promoting compounds in the gut microbiomes of mouse models of MS.

Blocking the ability of the rodents’ T cells, a type of immune cell that can cause inflammation, to express AHR stymied the production of those compounds in the animals’ guts — and reduced their inflammation.

“We may have found a more reliable route to promote a healthy gut microbiome.”

Andrea Merchak

Looking ahead: More research on how the immune system and microbiome interact is still needed. However, the UVA researchers believe that doctors might one day be able to reduce chronic inflammation in MS patients by improving their gut health with AHC-focused therapies.

“Due to the complexity of the gut flora, probiotics are difficult to use clinically,” said Merchak. “This receptor can easily be targeted with medications, so we may have found a more reliable route to promote a healthy gut microbiome.”

“Ultimately, fine-tuning the immune response using the microbiome could save patients from dealing with the harsh side effects of immunosuppressant drugs,” she added.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].