New material traps CO2 — and turns it into baking soda

A newly developed material could dramatically cut the cost of pulling carbon from the air — and it might also improve the health of our oceans.

Direct air capture: Reducing our greenhouse gas emissions isn’t going to be enough to avoid the worst predicted effects of climate change — we’re also going to need to remove and sequester carbon that’s already in the atmosphere.

Planting more trees (including fast-growing, carbon-hungry ones) can help with this, but we can also use a process known as “direct air capture” to remove CO2.

Typically, direct air capture systems use giant fans to pull air across a filter. Chemicals in the filter trap the carbon, while allowing the filtered air to exit the system. Heat is later applied to the filter to remove the pure CO2, which is then captured, and the filter is reused.

The captured carbon, meanwhile, can be used to make products, such as concrete, or it can be pressurized and liquified before being injected into the ground, where it will eventually turn into rock and remain trapped indefinitely.

The challenge: Today, there are fewer than 20 operational direct air capture systems, extracting a total of just 9,000 tons of carbon annually — and according to climate models, we need to scale that up to 10 gigatonnes per year by 2050, an increase of over a million-fold.

The major factor holding back direct air capture is cost.

As of 2019, it cost about $600 in technology and energy to capture one ton of CO2 (though companies in the industry say the cost will fall if the tech scales up). But for the process to be economically viable, experts say we need to get that down to under $100, since that’s about how much companies will pay for captured carbon.

“This material can be produced at very high capacity very rapidly.”

Arup SenGupta

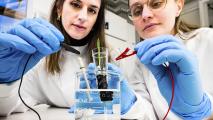

What’s new? Researchers at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania have now published a study detailing a material that could dramatically cut the cost of carbon capture.

Like the filters used in most direct air capture systems, it’s an amine-based material — meaning it contains nitrogen atoms — but it also includes copper. According to the team’s study, this allows it to absorb up to three times as much CO2.

“This material can be produced at very high capacity very rapidly,” lead author Arup SenGupta told New Scientist. “That definitely should improve the cost-effectiveness of the process.”

Seawater and baking soda: The new material could also cut costs after carbon is captured.

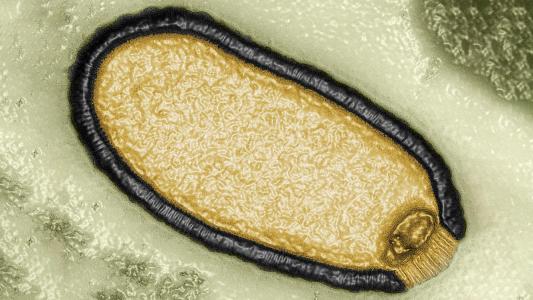

Instead of using heat to extract the trapped carbon and then pressurizing and liquifying it for storage — processes that add to the total cost — the researchers found they could just expose their material to seawater.

Seawater triggers a reaction that turns the carbon into sodium bicarbonate — better known as baking soda — which could be stored without any additional processing.

The material could potentially cut the cost of direct air capture down to less than $100 a ton.

The bonus: In theory, we could use this sodium bicarbonate in the oceans, where it might combat the acidification that’s being caused by our pumping of CO2 into the atmosphere.

Adding large amounts of baking soda to the oceans could have unintended consequences, though, so more research would be needed to ensure it’s safe, and even if it is, there would be regulatory hurdles to surmount before a plan could be put into action.

“Disposing of large tonnages of sodium bicarbonate in the ocean could be legally defined as ‘dumping,’ which is banned by international treaties,” Stuart Haszeldine, a carbon capture and storage researcher at the University of Edinburgh, told CNN.

Looking ahead: The researchers are now setting up a company to further develop their carbon-trapping material and are eager to begin testing it outside the lab — one thing they’ll need to look at is how many times the material can be reused.

If everything works as hoped, SenGupta believes his team’s material could cut the overall cost of direct air capture down to less than $100 a ton — potentially allowing us to finally scale up the tech to the levels we need.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].