Feeding insects to cattle could make meat and milk production more sustainable

The world’s population is growing, and so is the challenge of feeding everyone. Current projections indicate that by 2050, global food demand could increase by 59%-98% above current levels. In particular, there will be increased demand for high-quality protein foods, such as meat and dairy products.

Livestock producers in the U.S. and other exporting countries are looking for ways to increase their output while also being sensitive to the environmental impacts of agricultural production. One important leverage point is finding ingredients for animal feed that can substitute for grains, freeing more farmland to grow crops for human consumption.

Cattle are natural upcyclers: Their specialized digestive systems allow them to convert low-quality sources of nutrients that humans cannot digest, such as grass and hay, into high-quality protein foods like meat and milk that meet human nutritional requirements. But when the protein content of grass and hay becomes too low, typically in winter, producers feed their animals an additional protein source – often soybean meal. This strategy helps cattle grow, but it also drives up the cost of meat and leaves less farmland to grow crops for human consumption.

Growing grains also has environmental impacts: For example, large-scale soybean production is a driver of deforestation in the Amazon. For all of these reasons, our laboratory is working to identify alternative, novel protein sources for cattle.

Black soldier fly larvae

An insect farming industry is emerging rapidly across the globe. Producers are growing insects for animal feed because of their nutritional profile and ability to grow quickly. Data also suggests that feeding insects to livestock has a smaller environmental footprint than conventional feed crops such as soybean meal.

Among thousands of edible insect species, one that’s attracting attention is the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). In their larval form, black soldier flies are 45% protein and 35% fat. They can be fed efficiently on wastes from many industries, such as pre-consumer food waste. The larvae can be raised on a large scale in factory-sized facilities and are shelf-stable after they are dried.

Most adults in the U.S. aren’t ready to put black soldier fly larvae on their plates but are much more willing to consume meat from livestock that are fed black soldier fly larvae. This has sparked research into using black soldier fly larvae as livestock feed.

Already approved for other livestock

Extensive research has shown that black soldier fly larvae can be fed to chickens, pigs and fish as a replacement for conventional protein feeds such as soybean meal and fish meal. The American Association of Feed Control Officials, whose members regulate the sale and distribution of animal feeds in the U.S., has approved the larvae as feed for poultry, pigs and certain fish.

So far, however, there has been scant research on feeding black soldier fly larvae to cattle. This is important for several reasons. First, more than 14 million cattle and calves are fed grain or feed in the U.S. Second, cattle’s specialized digestive system may allow them to utilize black soldier fly larvae as feed more efficiently than other livestock.

Promising results in cattle

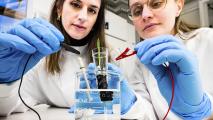

Early in 2022, our laboratory published results from the first trial of feeding black soldier fly larvae to cattle. We used cattle that had been surgically fitted with small, porthole-like devices called cannulas, which allowed us to study and analyze the animals’ rumens – the portion of their stomach that is primarily responsible for converting fiber feeds, such as grass and hay, into energy that they can use.

Cannulation is widely used to study digestion in cattle, sheep and goats, including the amount of methane they burp, which contributes to climate change. The procedure is carried out by veterinary professionals following strict protocols to protect the animals’ well-being.

In our study, the cattle consumed a base diet of hay plus a protein supplement based on either black soldier fly larvae or conventional cattle industry protein feeds. We know that feeding cows a protein supplement along with grass or hay increases the amount of grass and hay they consume, so we hoped the insect-based supplement would have the same effect.

That was exactly what we observed: The insect-based protein supplement increased animals’ hay intake and digestion similarly to the conventional protein supplement. This indicates that black soldier fly larvae have potential as an alternative protein supplement for cattle.

Costs and byproducts

We have since conducted three additional trials evaluating black soldier fly larvae in cattle, including two funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. We are especially interested in feeding cattle larvae that have had their fat removed. Data suggest that the fat can be converted to biodiesel, yielding two sustainable products from black soldier flies.

We are also studying how consuming the larvae will affect methane-producing microbes that live in cattle’s stomachs. If our current research on this question, which is scheduled for publication in the spring of 2023, indicates that consuming black soldier fly larvae can reduce the amount of methane cows produce, we hope it will motivate regulators to approve the larvae as cattle feed.

Economics also matter. How much will beef and dairy cattle producers pay for insect-based feed, and can the insects be raised at that price point? To begin answering these questions, we conducted an economic analysis of black soldier fly larvae for the U.S. cattle industry, also published early in 2022.

We found that the larvae would be priced slightly higher than current protein sources normally fed to cattle, including soybean meal. This higher price reflects the superior nutritional profile of black soldier fly larvae. However, it is not yet known if the insect farming industry can grow black soldier fly larvae at this price point, or if cattle producers would pay it.

The global market for edible insects is growing quickly, and advocates contend that using insects as ingredients can make human and animal food more sustainable. In my view, the cattle feeding industry is an ideal market, and I hope to see further research that engages both insect and cattle producers.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.