“Hydrogel” drugs could suppress HIV with minimal treatments

Since the HIV virus was discovered in the 1980s, prospects for people living with the disease have vastly improved. With the latest advances in antiretroviral (ARV) drugs — including cocktails of multiple drugs to prevent the virus from evolving resistance — patients who stay on treatment can now expect to live long, healthy lives after testing positive, with a very low risk of the disease progressing to AIDS later on.

The challenge: Even so, the ARV treatment still imposes an ever-present cost on patients’ quality of life. To maintain high enough levels of the drugs to suppress HIV in their blood, they need to follow strict treatment regimes – with each drug requiring a different dosage and dosing frequency.

For many people, the need to constantly keep track of such complex treatment schedules is stressful and difficult, and serves as a constant reminder of their condition.

The hydrogel: New research published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society describes the possibility of a far more subtle approach to delivering HIV treatment. In their study, Honggang Cui and colleagues at John Hopkins University describe how ARV drugs could be delivered directly into the bloodstream using injectable hydrogels.

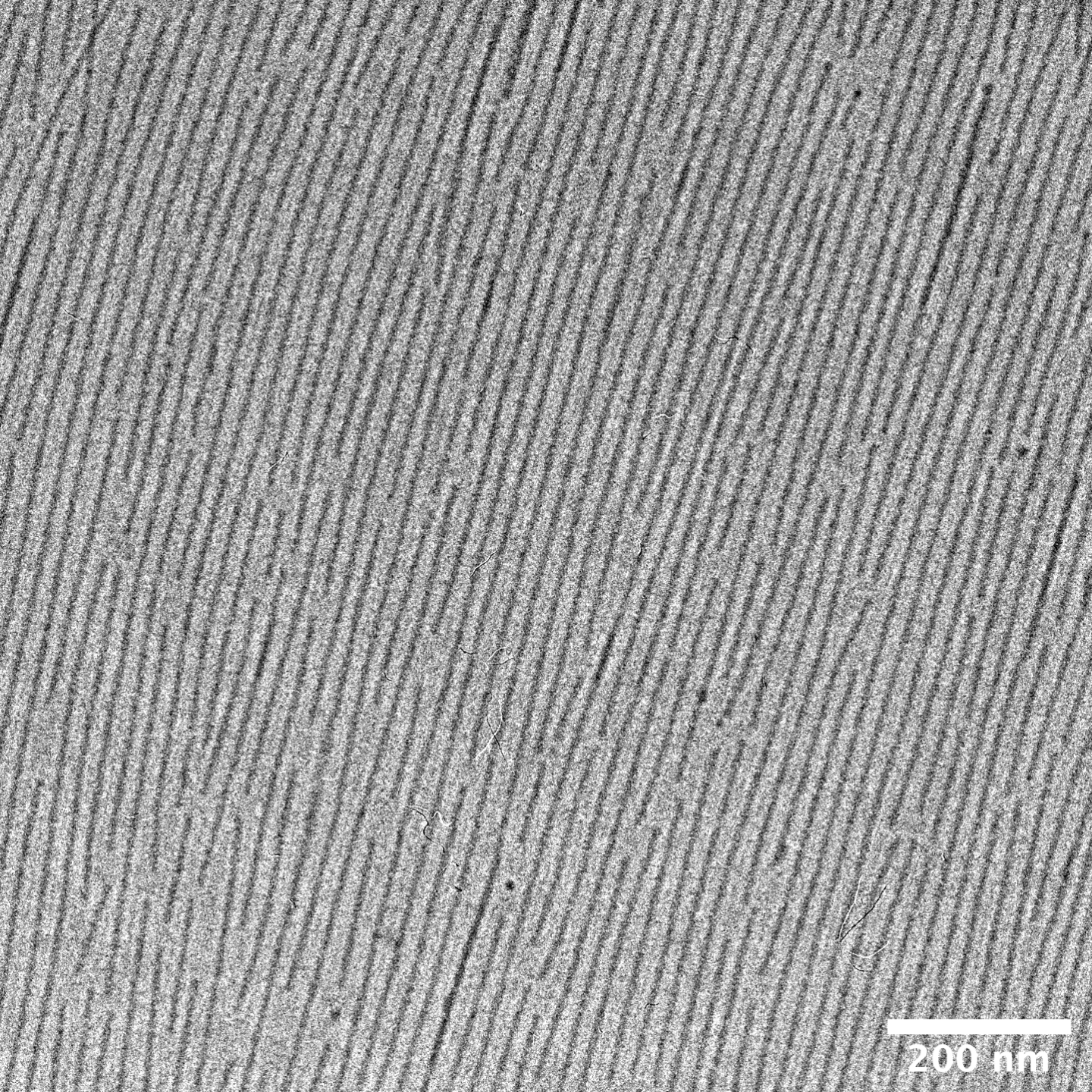

Widely used in medicine for their similarity with biological tissues, hydrogels are made up of 3D networks of polymer chains, which absorb and retain large amounts of water.

When injected, the material dissolves back into individual molecules of the anti-HIV drug lamivudine.

The experiment: Cui’s team engineered a series of specialized molecules based on lamivudine: a key ARV drug used to suppress replication of the HIV virus. These molecules featured a combination of water-attracting and water-repelling regions, which — under just the right conditions — caused them to spontaneously assemble themselves into a 3D hydrogel.

When injected inside the bloodstream, the material then gradually dissolves back into individual molecules of lamivudine.

The researchers injected their hydrogel directly under the skin of mice, then monitored levels of lamivudine in their bloodstreams over the following weeks. Just as they hoped, the hydrogel dissolved steadily and predictably over a period of 42 days, with the mice experiencing almost no visible side-effects. During that time, lamivudine remained at high enough levels in their blood to sustain effective ARV treatment.

The road to new treatments: The result is hugely promising, suggesting that hydrogel-based treatments may be safe enough to progress to human trials in the not-too-distant future.

Looking further ahead, Cui’s team suggest that even more advanced hydrogels could be programmed to deliver several different ARV drugs at the same time: with different molecules dissolving at different rates to deliver the appropriate dosages of different drugs.

If realized, these hydrogels would only need to be injected every few weeks, so that patients wouldn’t need to worry about keeping track of any confusing treatment schedules.

Even further, the researchers suggest that new hydrogels could be developed to treat other diseases – including hepatitis B, which often appears alongside HIV.

While trials may be closer than ever, the team’s approach is still a long way off from FDA approval as an alternative to traditional and proven ARV therapy. All the same, they are hopeful that their hydrogel-based treatments could one day help to improve the everyday lives of millions of people globally.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].