NASA thinks it may snow upside down on Europa

“Underwater snow” in Antarctica is revealing new insights about Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, which could help in NASA’s hunt for extraterrestrial life.

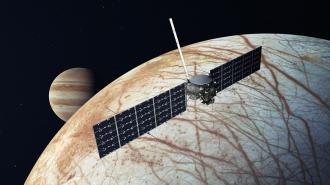

Europa Clipper: Three things are needed for life as we know it to exist: liquid water, organic compounds, and a source of energy — and scientists suspect Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has all three, making it one of the more promising targets in the hunt for extraterrestrial life.

NASA has already sent several spacecraft to Europa to capture close-up data, and it plans to launch its next probe in October 2024: the Europa Clipper.

Knowing the salinity of Europa’s water will help NASA judge the icy moon’s habitability.

The primary purpose of the mission is to determine whether there are places life could survive beneath Europa’s surface. As part of that objective, Europa Clipper will use a radar instrument to look past the moon’s icy shell and into what NASA suspects is an ocean of liquid water below.

The salinity of Europa’s water, and the ice covering it, will affect how deep the radar can penetrate and what sort of data it collects. Knowing just how salty the water is would also help NASA judge Europa’s habitability and predict what type of life the icy moon might host.

But right now, we don’t know the exact salt content of Europa’s ice or the water below it, which will make interpreting the Europa Clipper’s data more difficult.

The idea: We do have an analogue for Europa right here on Earth, though: Based on previous studies, researchers suspect the water just below an ice shelf in Antarctica is similar in temperature, pressure, and salinity to water just below the icy surface of Europa.

A team led by the University of Texas at Austin — which is spearheading the development of the Europa Clipper’s radar instrument — has now studied Antarctic ice formation to predict the saltiness of Europa’s ice.

“We can use Earth to evaluate Europa’s habitability, measure the exchange of impurities between the ice and ocean, and figure out where water is in the ice,” said co-author Donald Blankenship.

“It sets the stage for how we might prepare for Europa Clipper’s analysis of the ice.”

Steve Vance

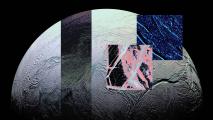

Underwater snow: There are two ways for water to freeze under an ice shelf. One is for it to freeze literally right under the shelf — that’s “congelation” ice. The other is for ice flakes to form deeper underwater and then float up to the shelf, like upside-down snow — that’s “frazil” ice.

When saltwater freezes, the ice always contains mostly water and very little salt, but frazil ice contains even less salt than congelation ice — and based on UT Austin’s calculations, this kind of underwater snow could be common on Europa.

The bottom line: If the UT Austin team is right, it would mean Europa’s icy shell is much purer than previously believed, which changes our perceived understanding of its strength, ability to transmit heat, and more.

“This paper is opening up a whole new batch of possibilities for thinking about ocean worlds and how they work,” said Steve Vance, a NASA research scientist, who was not involved in the study. “It sets the stage for how we might prepare for Europa Clipper’s analysis of the ice.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].