Jupiter’s hot “pizza moon” may contain life

NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which has been studying Jupiter and its large inner moons up close for the past six and a half years, is currently humanity’s most distant planetary orbiter. The giant planet and its stormy atmosphere were initially Juno’s main focus, but in the mission’s current extended phase, close fly-bys of the Jovian satellites are on the menu as well.

While Europa and Ganymede (the Solar System’s largest moon) have typically been of greater interest to astrobiologists due to their subsurface oceans, another Jovian satellite — hot, volcanic Io — has largely been dismissed as a possible abode for life now or in the past. That may be about to change, however. Juno recently passed by Io at a distance of 80,000 km, and over the course of this coming year will get much closer, within 1,500 km.

Heyo, Io

Most of what we know about Io dates from more than 20 years ago, when the Galileo spacecraft toured the Jovian system. A quick recap: Io is roughly the size of our Moon, but otherwise couldn’t be more different. Galileo found, among other things, an active lava lake (perhaps crusted over) and a lava “curtain,” along with active lava flows, calderas, mountains, plateaus, and plains.

Microbial growth is common in lava tubes on Earth no matter the location and climate, whether it’s ice-volcano interactions in Iceland or hot, sand-floored lava tubes in Saudi Arabia.

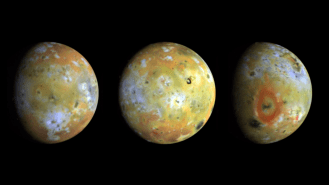

Recent simulations show that tidal heating on this most volcanically active body in the Solar System is keeping magma liquid below the surface. Some of Io’s volcanic eruptions are so violent that lava is ejected hundreds of kilometers into space. While the average surface temperature of -130° C is very cold, temperatures near volcanic centers reach up to 1,600° C or more, hot enough to keep the lava liquid. Some volcanic vents eject gaseous sulfur dioxide into the ultra-wispy atmosphere, which later condenses as frost on Io’s surface. Hot lava flows pour over some of the sulfur dioxide snowfields. The characteristic yellow / orange / red surface of Io, dominated by different types of sulfur, earned the moon its nickname among scientists: the Pizza Moon.

The moon’s surface is constantly being reworked, which means that we see no fresh impact craters. Early in its history, Io may have held as much water as Europa or Ganymede, since it formed in a region of the Solar System where water ice was plentiful. In those early days, the combination of liquid water and geothermal heat could have led life to develop. However, due to Jupiter’s unforgiving radiation and tidal heating, Io subsequently lost most if not all of its water, and the surface became uninhabitable.

What lies beneath

What about the subsurface? Water and carbon (at least in the form of carbon dioxide) may still be abundant there, although the driving force for Io’s volcanic vents seems more likely to be sulfur dioxide or other sulfur gases. In principle, geothermal activity and reduced sulfur compounds could provide microbial life with sufficient energy sources. Hydrogen sulfide in particular is probably common below the surface. On Earth, life prefers dynamic environments over stagnant locations like the Moon, which is a lifeless rock. That said, Io may be a little too violent, even underground.

If we imagine the possibility of underground life on Io, its environment would have to be radically different from what we see at the surface. A suitable habitat would have to provide protection from radiation, and temperatures would have to stay sufficiently warm and constant. The environment would have to trap moisture somehow and provide nutrients such as sulfide and hydrogen sulfide that could be oxidized to sulfur dioxide or sulfates.

At a 2004 conference in Iceland, followed by a paper six years later, I suggested that lava tubes could take over that function. They should be common on Io, given all the volcanic activity. Microbial growth is common in lava tubes on Earth no matter the location and climate, whether it’s ice-volcano interactions in Iceland or hot, sand-floored lava tubes in Saudi Arabia. Lava tubes are the most plausible cave environment for life on Mars, and caves in general are a great model for potential subsurface ecosystems.

A hard life on Io

Even so, the scarcity of water on Io is a problem. Part of the reason water is such a useful solvent for life on Earth is because it’s so abundant. But it would have become scarcer and scarcer on Io since the early days of the Solar System. If there isn’t enough water left for life to use as a solvent, sulfur compounds might be able to stand in.

The most likely alternative would probably be hydrogen sulfide due to its many chemical similarities with water. It can dissolve many substances, including organic compounds. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) remains liquid at temperatures from -86° to -60° C (at one Earth atmosphere of pressure), which matches temperatures that might prevail in the shallow underground on Io. In fact, hydrogen sulfide might turn liquid when overhead lava warms the subsurface layer. That might activate any dormant forms such as spores, if they exist, creating an exotic subsurface microbial ecosystem. Since hydrogen sulfide is also soluble in water, it could also supplement whatever small amount of water is still present on Io.

Suggesting an alternative solvent for life is always very, very speculative. But if we’re going to imagine life on other worlds, we have to keep free from preconceptions and stay open-minded. The main problem with testing this kind of hypothesis is that we can’t simply land and look — the radiation and volcanic activity on Io make this all but impossible. Orbiters are the next best alternative, and Juno should give us some more grand views of this intriguing moon, as well as better knowledge of its surface chemistry. And if the proposed Io Volcano Observer makes it to the launch pad, we could learn a lot about tidal heating as a fundamental planetary process, and maybe even as an engine for the development of extraterrestrial life.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.