Drug for MS may be able to treat Alzheimer’s, too

A drug approved to treat multiple sclerosis (MS) could be a promising Alzheimer’s treatment, according to suggestive early experiments with mice and human brain samples.

“We’ve uncovered that a medication already on the market…can reduce one of the hallmarks of this disease: neuroinflammation,” said principal investigator Erhard Bieberich from the University of Kentucky.

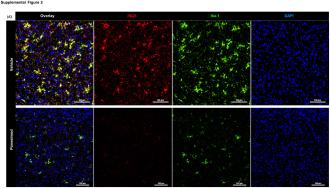

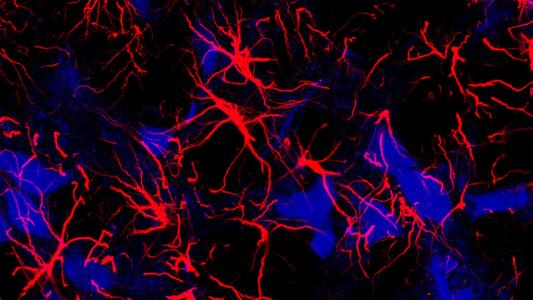

The background: Microglia are the main immune cell of the central nervous system, and one of their jobs is to clear clumps, or “plaques,” of toxic amyloid-beta protein from the brain.

For reasons that aren’t entirely understood, microglia don’t work the way they’re supposed to in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s — they become overactive, releasing chemicals that cause brain-damaging neuroinflammation, but still don’t stop amyloid-beta plaques from building up.

“We’ve uncovered that a medication already on the market…can reduce one of the hallmarks of this disease: neuroinflammation.”

Erhard Bieberich

The idea: Based on earlier studies, researchers at the University of Kentucky (UK) suspected that abnormal amyloid-beta proteins trigger inflammation by acting on a receptor called “SPNS2” in microglia cells.

The MS drug ponesimod targets this same receptor on immune system cells to prevent neuroinflammation. That prompted the researchers to wonder if it might be able to treat Alzheimer’s as well.

The study: To test the theory, the UK team gave the drug to mouse models of Alzheimer’s and then measured their brain activity. They also gave the rodents a spatial memory test before and after treatment.

As hoped, the MS med appeared to stop the microglia from overexpressing the inflammation-triggering chemicals, reducing neuroinflammation. At the same time, it also appeared to increase the clearance of amyloid-beta plaques from the animals’ brains and improve their spatial memory.

“We reprogrammed microglia into neuron-protective cells that clean up toxic proteins in the brain.”

Zhihui Zhu

Tests on brain tissue samples from people who’d had Alzheimer’s produced results consistent with those of the mouse experiments, according to the researchers.

“In our study, we reprogrammed microglia into neuron-protective cells that clean up toxic proteins in the brain, reduce Alzheimer’s neuroinflammatory pathology, and improve memory in the mouse model,” said first author Zhihui Zhu.

Looking ahead: Many treatments that work in mice don’t translate to humans, and there has been a lot of criticism of mouse models of Alzheimer’s, in particular. However, the fact that ponesimod is already FDA approved means it’ll be much easier to run a clinical trial of it in Alzheimer’s patients than a brand-new drug would be.

Even if this particular drug isn’t effective against Alzheimer’s symptoms, other in-development treatments targeting microglia are showing promise, suggesting that these errant immune cells just may be the key to treating this devastating disease.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].