Closer to the Sun: NASA’s Parker Solar Probe

You ever play Super Mario Bros. 3 as a kid? You may remember the surprise when, during your adventures through the desert, the sun — wearing an angry scowl — shook itself to life and began dive bombing the world’s most turtle-averse plumber.

Don’t worry, the star won’t be falling from the skies anytime soon. But new data from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe reveals that the sun is, indeed, kind of crazy. Rogue waves, spiraling space winds, fast-flipping magnetic fields: far from a staid shining ball, the sun is kinetic in its fury.

But the biggest revelation from the Parker Solar Probe may be just how much there is about solar activity that we don’t know.

“It’s a very complicated environment that we’re talking about,” says Colin J. Joyce, a postdoc research assistant at Princeton involved with the project. “There’s so many processes that could be going on.”

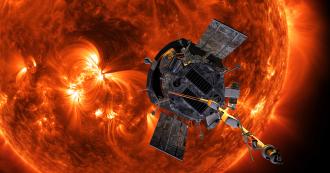

The Parker Solar Probe’s mission is to get closer to the sun than we ever have before. It has already been twice as close as the previous record, and it will be three times closer by the time its mission is done. There, it is gathering solar wind data, information about the sun’s magnetic fields, and measurements of the high energy particles rocketing around.

Getting within a blistering 4 million miles of the sun’s surface (almost 96% of the way there, from Earth), it will explore an area of heat and radiation more intense than any probe before it has faced. (NASA says the probe’s heat shield will be protecting it from temperatures approaching 2600℉ on its closest pass.)

Launched in August 2018, the first batches of data from the probe were recently written up in four papers in Nature. That data contains new insights completely outside the expected — elements of solar activity we had no idea existed before. The probe’s surprises are helping scientists to piece together the puzzles of the corona and the basic functioning of the sun. With this information we may better understand the stars that dramatically impact our universe, as well as the space weather from the sun that impacts the Earth.

“I’ve been saying for years we’re going someplace new, we’ll be seeing something unexpected,” says Justin Kasper, professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at Michigan, a co-author on three of the papers.

Among the most exciting is new solar wind data. This may help unlock the mysteries of these hot gas plumes that diffuse throughout the solar system. Solar winds are usually pretty calm by the time they reach Earth. The Parker Solar Probe has revealed that the sun stirs up the solar winds far further from its surface than scientists thought. This may help us better understand the evolution of the sun.

Observed near Earth, the solar wind is a relatively uniform flow of plasma, with occasional turbulent tumbles. But by that point it’s traveled over ninety million miles — and the signatures of the Sun’s exact mechanisms for heating and accelerating the solar wind are wiped out. Closer to the solar wind’s source, Parker Solar Probe saw a much different picture: a complicated, active system. Credit: NASA Goddard/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez

“On very, very, very, very long time scales, this affects how the sun slows down its rotation,” says Nicholeen Viall, a research astrophysicist at NASA and a member of the scientific team for two of the Parker’s instruments.

Understanding that will help us learn about how the sun and other stars wind down their life cycles. Joyce compares the effect to sticking out your arms while spinning in an office chair.

The Parker’s data has more immediate implications as well. Understanding the conditions near the sun where solar storms are formed can help protect the Earth. The sun impacts us beyond providing heat and light. Solar activity can kick up like a wind gust. The radiation those winds carry can damage satellites and pose a threat to astronauts. Coronal mass ejections (CME) are huge chunks of the corona shot free that have the potential to hit the Earth. These can wreak havoc on our electrical systems.

One CME in 1859, called the Carrington Event, caused the Northern Lights to be seen as far south as Cuba and Honolulu and sparks to leap from telegraph equipment. Imagine the potential damage for a world far more reliant on technology today.

If you think of solar weather like a hurricane, the solar wind data from the Parker Solar Probe is like the meteorological measurements that help us to predict and track those massive storms. Being able to predict these storms ahead of time could mean the difference between a safe and successful mission to the moon or Mars or putting astronauts at immense risk.

Parker indicated that the solar magnetic field embedded in the solar wind flips in the direction. These reversals — dubbed “switchbacks” — last anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes as they flow over Parker Solar Probe. During a switchback, the magnetic field whips back on itself until it is pointed almost directly back at the Sun. Credit: NASA Goddard/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez

Inside the tumultuous corona, the Parker also revealed rogue waves which rip through space so fast they flip the magnetic field. These waves could not have been measured without getting this close, Kasper says, and they could be part of how the corona gets hotter than the sun’s surface, an intriguing mystery.

The entire environment around the sun is filled with high energy particles, barely understood waves, and other events found nowhere else near the Earth. And with every orbit, we’re going to learn more, says Viall.

All of the researchers were excited and a bit bewildered by the data they saw. Watching the information come in, Joyce felt a part of history.

“Getting closer to the sun is a big step towards figuring out what’s actually going on here,” Joyce says.