Microbiome-safe method could head off Staph infection

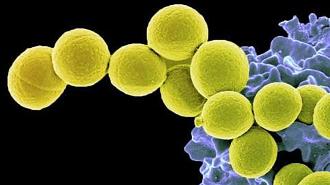

Researchers have developed a possible way to keep colonies of Staphylococcus aureus — the bacteria behind MRSA — in check without doing damage to the beneficial microbes living in our gut microbiome. Such a therapy could help reduce the risk of infection while maintaining the delicate ecosystem inside our digestive tract.

Their technique uses a digested probiotic of Bacillus subtilis, a beneficial bacteria. When taken orally, the B. subtilis successfully and safely reduced S. aureus colonies in both the gut and nose in a phase 2 clinical trial.

“The probiotic we use does not ‘kill’ S. aureus, but it specifically and strongly diminishes its capacity to colonize,” Michael Otto, a senior investigator at the National Institute of Allergic and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) who led the study, said.

“We think we can target the ‘bad’ S. aureus while leaving the composition of the microbiota [the organisms living in the microbiome] intact.”

Researchers have developed a possible way to keep colonies of Staph in check without doing damage to the beneficial microbes living in our gut microbiome.

Decolonization: With the rise of antibiotic-resistant superbugs, clinicians and researchers have begun a fevered hunt for new, effective ways to kill bacteria — or prevent disease from starting in the first place.

Despite being the deadliest superbug in the US (as its alter ego MRSA), S. aureus can also be commonly found in or on the nose, gut, and skin of healthy people, where it just does its thing. Such bacteria are considered a “colony.” Have your protective skin barrier broken, however, or your immune system suppressed, and that colony can become pathogenic, potentially causing severe disease.

“Decolonization” looks to get out ahead of this problem, by eliminating currently harmless but potentially dangerous colonies of bacteria, before they mutate or have a chance to become an issue.

But S. aureus decolonization has its drawbacks, the NIAID researchers wrote in their study, published in The Lancet Microbe.

Topical methods aimed at the nose and skin have had “little success,” and decolonizing the gut would be “ill advised” due to the large amount of antibiotics needed. Using antibiotics like this is essentially carpet bombing the microbiome — killing countless helpful bacteria, as well as risking additional drug resistance in some that survive.

That looks all the more ill advised as researchers develop a better understanding of the importance of the gut microbiome to human health. When the array of bacteria inside your digestive tract are in balance, they can help keep the immune system at the ready, break down potentially toxic food chemicals, and help digest certain vitamins and enzymes.

Throw the microbiome out of whack, however, and “bad” bacteria may proliferate instead. For this reason, the Infectious Diseases Society of America discourages using oral antibiotics to decolonize S. aureus in the gut.

Using antibiotics to decolonize staff can damage the helpful bacteria of the gut microbiome.

Going for the gut: To solve this problem, the team turned to probiotics, rather than antibiotics. Probiotics contain harmless living microbes to introduce to the microbiome. In this case, the researchers used a bacteria, B. subtilis.

B. subtilis is promising because it can be ingested as spores — an extra-hardy form that can survive the acid-soaked and enzyme-rich ride through the stomach and make it to the intestines, where it can temporarily set up shop.

A group led by Otto, the NIAID investigator, had previously found a sensing system that S. aureus needs to use to grow within the gut. B. subtilis produces molecules that interfere with that system, hamstringing its ability to reproduce.

The trial: To test their probiotic, microbiome-friendly decolonization technique, the team conducted a phase 2 clinical trial in Thailand with colleagues from the Rajamangala University of Technology Srivijaya and Prince of Songkla University.

The study enrolled 115 healthy people who all were natural carriers of S. aureus. They were split randomly into groups, with 55 receiving the B. subtilis probiotic once a day for four weeks, and a 60-person control group getting a placebo.

At the end of four weeks, the researchers measured S. aureus levels in the nose and gut of participants. There was no reduction in the colonies in placebo patients, while the probiotic group showed a 96.8% reduction in the gut — measured via stool samples — and a 64.5% reduction in the nose.

To solve this problem, the team turned to probiotics, rather than antibiotics.

“Intestinal S. aureus colonization has been evident for decades, but mostly neglected by researchers because it was not a viable target for antibiotics,” Otto said. “Our results suggest a way to safely and effectively reduce the total number of colonizing S. aureus and also call for a categorical rethinking of what we learned in textbooks about S. aureus colonization of the human body.”

While the B. subtilis may take longer to work than antibiotics, it could also be used longer as it seems to cause no harm in patients.

The team plans to continue researching their technique with larger and longer clinical trials.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.