Mouse embryos grown in space for the first time

Japanese researchers have confirmed that mouse embryos can develop normally in space — for a short period of time, anyway. The experiment suggests that off-world reproduction may not be impossible for future astronauts.

Reproduction in space: Because Mars is usually around 140 million miles away, Mars astronauts will likely spend years away from Earth, which means they could potentially get pregnant and give birth before their scheduled flights home. If we decide to try populating the Red Planet, Mars colonists might even want to reproduce away from Earth — but right now, we don’t know whether that’s safe or even possible.

“The risks of spaceflight are (reasonably) well-understood, but the consequences of those risks on conception, pregnancy, birth, and development are barely understood at all — in any species, but particularly in mammals, and even more so in humans,” Gary Strangman, a lead scientist at the Translational Research Institute for Space Health, told Axios.

“[This is] the first-ever study that shows mammals may be able to thrive in space.”

Wakayama et al.

What’s new? To start to unravel the mystery of how microgravity, radiation, and other environmental factors might affect human reproduction in space, scientists from Japanese research institute Riken and the University of Yamanashi sent 720 two-celled mouse embryos to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2021.

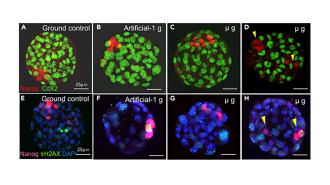

After thawing the frozen embryos, ISS astronauts cultured half in microgravity and half in artificial gravity for four days — that’s the maximum amount of time mouse embryos can survive outside the womb. They then preserved the embryos for the return flight to Earth.

The Japanese team has now reported that the ISS embryos were less likely to survive than controls they cultured on Earth — less than 30% of the space embryos developed beyond the two-cell stage compared to more than 60% of the controls.

However, the ISS embryos that did survive the experiment appeared to develop normally during their brief time in space — there was no evidence that space radiation damaged the embryos’ DNA or that microgravity affected their ability to differentiate into different types of cells.

“[This is] the first-ever study that shows mammals may be able to thrive in space,” the researchers said in a joint statement, according to AFP.

Looking ahead: We are still far from knowing whether reproduction in space will be safe (or possible) for humans.

The next step for the Japanese team will be to see if mouse embryos sent to the ISS for a period of time can impregnate mice on Earth and lead to the birth of healthy pups. Lead researcher Teruhiko Wakayama told New Scientist they’d also like to send mouse sperm and eggs to the ISS to see if embryos can be created in space.

“We intend to perform conception and early embryo development in space.”

Egbert Edelbroek

Netherlands-based company SpaceBorn United might beat them to that, though.

It has developed a prototype device to create and incubate embryos in space, which it plans to send into low-Earth orbit for the first time in 2024. The company’s goal is to test the device using rodent cells at first, before moving on to experiments with human eggs and sperm.

“We intend to perform conception and early embryo development in space,” SpaceBorn’s CEO Egbert Edelbroek told BBC Science Focus. “If we want to have human settlements, for example, on Mars, and if we want to make those settlements really independent, that requires solving the reproduction challenge.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].