Meet the social entrepreneurs shaking up solar

Even at a young age, Dana Clare Redden considered herself an “Earth nut,” playing in the woods, collecting crawdads, and devouring every episode of Captain Planet. When she got an aquarium and goldfish, she was stoked. It would be her first lesson in how to take care of the natural world — a lesson that stuck with her decades later.

To make the fish feel at home, Redden filled the tank with stones collected from a nearby riverside. Almost immediately, all the fish died — driving home the realization that her small town wasn’t as idyllic as it felt.

From above, the region — in the heart of Pennsylvania coal country — looks like patches of beautiful green earth, dotted with lakes and rolling hills. But the area is known for what’s under the surface: more than fifty million tons of coal have been extracted from the earth.

“We would play in the woods. We would play in the creeks. We would catch crawdads. And some rivers were safe and others were, ‘Whoa, don’t go there,'” she says, describing orange rivers, damaged by acid mine drainage, that smelled like rotten eggs. Many of the adults in her life had respiratory issues like mesothelioma, which Redden says is “just something that people were used to living with.”

Now Redden owns Solar Stewards, a social enterprise to help disenfranchised and vulnerable communities access the benefits of solar energy. Climate change and lack of access to energy technology in rural communities exacerbate the burdens that low-income and minority populations face.

But Redden and other rural leaders with deep roots in their communities have innovative plans for long-term transformation.

“Matchmaking” for the climate

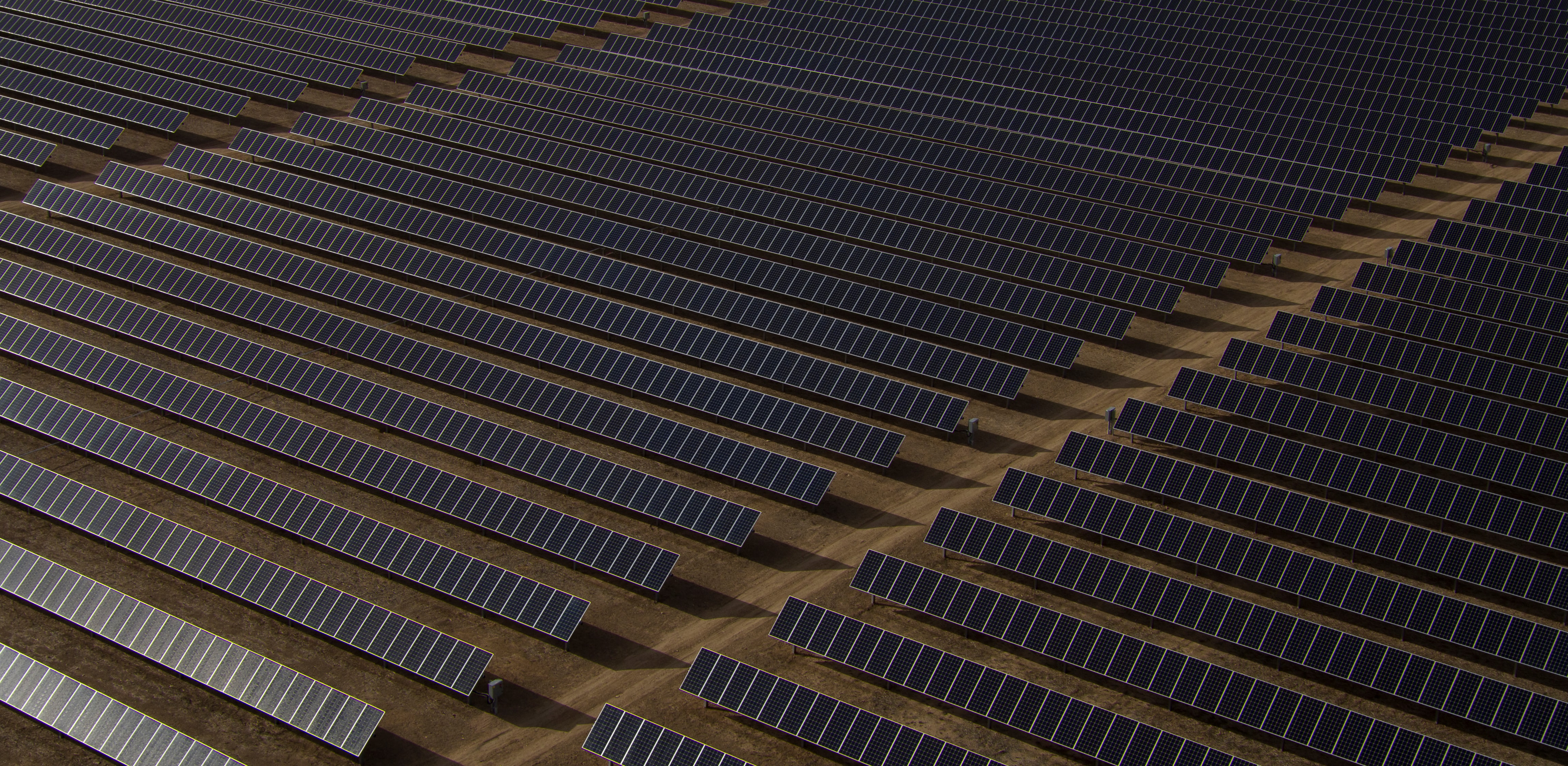

You could call Redden a matchmaker — showing local groups and big corporations why they need each other. With Solar Stewards, she connects corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs with impact money to build solar arrays on churches, senior living homes, grocery stores, and other organizations. In doing so, she helps businesses bring renewable energy to underserved BIPOC communities.

Last year, she connected a telecom company with a school. The company needed to meet a green energy goal, so Redden helped them install solar panels on an inner-city school campus — saving the school money and providing a real life STEM learning opportunity. But she didn’t go from collecting crawdads to building solar capacity overnight. First, she had to pay her dues as a solar panel salesperson. Going from home to home allowed her to sit around the dining table and talk to people.

“I felt like I bonded with regular folks, and it really opened my eyes, she says, “but I’m looking at their kids like, ‘they will never go to college if I sign this deal.’ They’re going to be trying to clean up this bad transaction for years,” she says.

That is when she saw the opportunity in the corporate sector of renewable energy. If corporations needed to invest in green energy to meet climate goals, why not have them buy it from people who don’t otherwise have access?

“It’s about making sure we don’t leave people behind. And that we don’t create sacrifice zones in order for ourselves to have the amenities that we need.”

Dana Clare Redden

Typically when corporations pledge to go 100% renewable energy, they buy renewable energy credits from utility-scale solar or wind farms — massive solar arrays, unlike the distributed solar energy sources Redden had been selling with rooftop solar panels.

So, she started aggregating these small projects to scale them up, helping them compete with utility-scale companies.

At first, corporations weren’t buying it.

“‘Bless your heart,’ as they say in Georgia. Everyone was looking at me like I was crazy,” she says, “Now everybody gets it, which is a beautiful moment.”

Many communities on the front lines of climate and socioeconomic inequalities face persistent injustices. Last year, Congress authorized the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, a $1.2 trillion infrastructure program that includes programs aiming to bring resources and capacity to areas historically underrepresented in these investments, such as BIPOC communities, rural areas, and small businesses — encouraging news for entrepreneurs like Redden, looking to make their views heard.

But a lot of work needs to happen before solar adoption penetrates Black communities, and boots-on-the-ground organizers will be needed to help move the needle.

A rallying cry for community solar

Kristal Hansley is the CEO of WeSolar, a community solar farm that provides low- and moderate-income families with affordable energy.

Most people are familiar with rooftop solar — panels sitting atop a home providing power or energy credits to the household. But for people with rental homes or roofs that aren’t suitable for it, solar panels aren’t even an option.

And, for the rest, the upfront cost of solar panel installation can be a significant barrier. (Hence the costly financing deals that Redden saw in the direct-to-consumer industry.)

Community solar, according to Hansley, can help with that. Customers can buy or lease panels from a neighboring solar farm instead of buying panels for their own roof. These panels will add energy to the grid, which ultimately helps power customers’ houses and the wider community. As a result, they get credits on their energy bills. And community solar doesn’t require homeownership or credit — removing the hurdles to getting renewable energy that many households encounter.

But access to solar energy isn’t only related to income or homeownership. It’s also a matter of reaching your target market, which often means more diverse representatives.

“The representation needs to reflect the people that you’re trying to target,” she says, adding that if you Google-image “community solar staff,” you’ll see the stark reality of representation. (I tried it. It’s true).

“That is exactly the reason why there’s a lot of issues as far as onboarding underrepresented communities and why there’s a cultural competency lag, and why there’s this gap. You need to incorporate diversity in the sector.”

Access to solar expands with diversity

Indeed, white males dominate the industry. According to the 2019 U.S. Solar Industry Diversity Study, 88 percent of top executives are white, and 80 percent are men. The industry’s lack of diversity could be trending business choices in favor of white populations. In a 2019 study, Deborah Sunter, an engineer at Tufts University, compared the number of homes with rooftop solar panels between neighborhoods primarily divided by race or ethnicity. She discovered that Black and Hispanic communities had many fewer rooftop solar panels.

Income and property ownership discrepancies are frequently blamed for this inequality. A legacy of redlining, zoning, and discriminatory practices in mortgage financing means fewer people of color own their homes or have access to financing.

Sunter, however, wasn’t satisfied with this explanation. So she opted to dig a little deeper.

She discovered that there is still a considerable racial and ethnic disparity even after accounting for income and homeownership differences. When comparing households of the same income level, predominantly white neighborhoods have 21% more rooftop solar than Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Controlling for rates of homeownership, the difference was 37%.

The study shows that even relatively prosperous areas of color have less rooftop solar — demonstrating that it is not simply about income.

“Justice and equity are actually at the forefront and one of the challenges preventing widespread adoption [of renewable energy],” she says.

Indiana University’s Sanya Carley, who studies equity and justice in the U.S. energy transition, adds that procedural justice — having more diversity “at the decision-making table” — is incredibly important.

“It is a race story… Making sure to include neighborhoods and communities of color in [the energy transition] is just absolutely fundamental.”

Sanya Carley

“It is not an income story, it is a race story,” she says. “Being mindful of who’s actually involved, and making sure to include neighborhoods and communities of color in [the energy transition] is just absolutely fundamental.”

That’s where Hansley comes in. She says the lack of diversity in the industry leads to a “cultural competency lag” — the capacity to understand and communicate with individuals from other cultures other than one’s own.

“If you’re sending someone outside the community to go knock on doors, and promise them savings, when two weeks ago someone did the same thing and bamboozled their 80-year-old grandmother — they just don’t believe you,” she says.

So Hansley is putting in the time — talking to as many people as possible about the benefits of community solar. Instead of simply building a smart plan for reliable, affordable energy, her work is founded on trust. She argues that the solar industry’s inability to recruit low- to moderate-income clients and people of color stems from a lack of trust.

“I don’t get to just run a solar company, not as a Black woman. My counterparts can just be CEOs. I have to run a solar company and teach at the same time,” she says. “That is just where we are.”

So, she hits the pavement — teaching about solar energy, giving presentations at community events, and knocking on doors.

She sees this as the groundwork for a new vision of community solar — where all aspects of the supply chain, from financing to site selection, involve the community.

Getting down to the basics

Energy is a basic need. It keeps refrigerators running and food fresh, medical devices powered, and homes warm or cool. Sometimes it can mean life or death.

High energy bills have always burdened low-income households and communities of color. According to a report by Ariel Drehobl, Lauren Ross, and Roxana Ayala for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, Black, Native American, and Hispanic families spend 20-45% more as a share of their income on energy bills than white households.

Among very low-income families, with incomes below half of the federal poverty line, some households may be spending as much as 50% of their income on home energy bills, according to Jordan Wirfs-Brock, a data journalist at Inside Energy.

This means communities of color and low-income families, many of whom live in rural America, are especially burdened by utility costs and face a higher risk for energy shut-offs. These communities could benefit by having a low-cost energy source like rooftop solar. Yet, government resources and subsidies for clean energy investments, like weatherizing homes, installing solar panels, and electric vehicles, disproportionally go to people with higher incomes.

Rural areas account for 86% of communities in the United States that experience chronic poverty. In many of those areas, the bulk of the populations are people of color. And, as Sunter points out, even as some communities of color are gaining access to solar power, it tends to be third-party-owned systems. “There’s still a disparity that exists in the quality of the ownership or the financial benefit that they get from participating in solar,” she says. Millions of dollars are invested in utility-scale solar arrays in rural areas, but very little of that money benefits the local community. Instead, the bulk of the profits go to a few investors.

Ajulo Othow, founder and CEO of EnerWealth Solutions, sees rural America as having a crucial role in tackling climate change. In the rural Southeast, she places solar energy installations on land owned by Black people. Her focus is on small-scale projects where local landowners own a larger share of the profit.

She echoes Hansley’s view that the solar industry’s inability to recruit people of color stems from a lack of trust.

“African American landowners may be more skeptical of these kinds of projects, or any project that could jeopardize their land because of the amount of land loss that’s been experienced by African American landowners through sometimes less than ethical or legal means,” she says.

“The transition to clean energy is one that we will make. It’s going to be important that we also help our economy be resilient and help our economy grow. Investments in rural communities can do that.”

Ajulo Othow

Like Redden and Hansley, much of Othow’s work gives people confidence in unconventional solar investments. The benefits are numerous. Minority landowners and small farmers can save on electricity while earning seven times what they could make by using that land for crops.

“The transition to clean energy is one that we will make,” she says. “In that transition, it’s going to be important that we also help our economy be resilient and help our economy grow. Investments in rural communities can do that.”

Looking forward

Projects like Redden’s Solar Stewards, Hansley’s WeSolar, and Othow’s EnerWealth Solutions are a one-two punch for climate change and racial inequality. Asked if it is crucial to address the challenges in tandem, they unanimously agree — yes.

Ensuring that people of color have access to solar power broadens the market share. This has the double benefit of maximizing rooftop solar and reducing disparities through tax credits and low-cost electricity. When it comes to the large amounts of money companies are spending on their climate strategy, Redden says they should set aside a portion for the equity piece.

“Carve out a bit of your carbon reduction strategy to include environmental justice and equity and access from renewables — you can do it all at the same time.”

Carley agrees.

“It’s about making sure we don’t leave people behind. And that we don’t create sacrifice zones in order for ourselves to have the amenities that we need.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].