Research: inflammation and mortality may be caused by low “psychological well-being”

The Japanese word ikigai translates roughly to “to live the realization that one hopes for” or “that which makes life worth living.” It’s a concept that refers to the intersection of what you love, what you are good at, what the world needs from you, and what you can get paid for. In essence, it is what one’s purpose in life is. Now, new research published in the journal JAMA Network Open shows that having a purpose in life is linked to living longer and healthier. Rather than Japan’s ikigai, this article defined purposeful living along more Western terms as “a self-organizing life aim that stimulates goals.”

This study used data from the Health and Retirement Survey, or HRS. Starting in 1996, the HRS has been administered to about 20,000 individuals over the age of 50 every two years and includes a slew of questions on demographics, physical and mental health, and other subjects. Critical to this research, the HRS began incorporating survey questions designed to measure life purpose in 2006, such as asking participants to indicate how strongly they agreed or disagreed with statements like “I enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them a reality” and “my daily activities often seem trivial and unimportant to me.”

This study specifically looked at the nearly 7,000 people who received the modified HRS in 2006 and met the study’s inclusion criteria. The researchers crafted a life purpose score based on the participants’ answers and followed-up with the participants five years later. During this period of time, 776 of the study participants had died. After conducting a statistical analysis, the researchers found that individuals who scored low for life purpose were more than twice as likely to have died in the five years after 2006.

What’s behind this finding?

It could be that this result was a case of reverse causality; rather than having low life purpose and subsequently dying, these individuals could have had, say, a life-threatening disease that caused them to feel as though their life had no purpose. But incredibly, the result still held when individuals with chronic and fatal conditions were excluded from the analysis, though slightly weakened. The researchers also took into account other variables that might affect life purpose and mortality, such as depression, optimism, anxiety, social participation, and so on — it seems as though not having a purpose in life can be fatal.

Overall, individuals with low life purpose scores died due to cardiovascular and digestive tract conditions. But if there really is a connection between life purpose and mortality, what’s the cause?

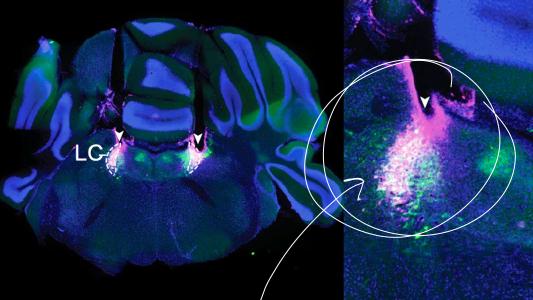

The authors speculated that inflammation may be responsible. Purposeful living is a significant contributor to overall well-being, and research has shown that stronger well-being is related to the reduced expression of genes that code for inflammation and with reduced cortisol levels, which is the hormone responsible for stress. Evidence exists, too, that higher levels of inflammatory proteins are associated with increased mortality. It could be that having no purpose in one’s life leads to chronically higher levels of inflammation. Researchers believe that chronic inflammation is behind a number of serious conditions, like coronary artery disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and cancer.

Lead author Aliya Alimujiang clarified the big picture. “There seems to be no downside to improving one’s life purpose, and there may be benefits,” she said. But this begs the question of how one can improve one’s life purpose. “Previous research,” said Alimujiang, “has suggested that volunteering and meditation may improve psychological well-being.” Exercise and social interaction has also been shown to improve well-being. But in addition to these strategies, one can simply try to find a purpose for living. Of course, that’s not so easy.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.